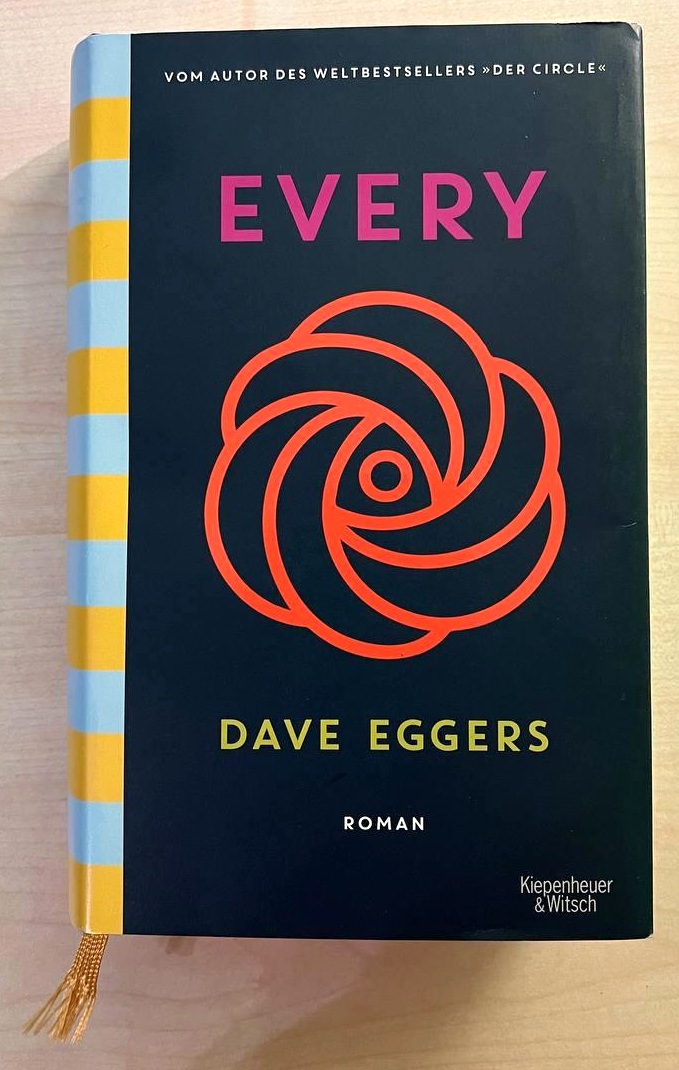

Musings on Dave Eggers' "The Every"

Posted: 18th November 2021Introduction

I just finished Dave Eggers' new book The Every. It doesn't happen all too often that I find a piece of contemporary fiction to be that captivating, entertaining, timely, and thought-provoking at the same time. Suffice to say, I definitely enjoyed it. In this post, I want to share some points I found particularly interesting, as well as some musings on them.

Objectivity in an algorithm's judgement?

A recurring topic in the story is the idea of using (not otherwise specified) algorithms to judge aesthetic beauty (be it of a piece of art, a book, a movie, or even a person's face), the ethical correctness of a product or service, or the truthfulness of a person or social interaction. In the story, the temptation for using such algorithms stems from a desire for objectivity, following the general idea that human taste is subjective (and thus "fallible"), whereas "numbers don't lie."

Of course, there are some obvious weaknesses to this argument: First, the attempt to quantify subjective taste in an objective manner naturally is doomed to fail, as this is not something objectively quantifiable in the first place. Second, if we start to use an algorithm to judge whether something is "good", "right", "beautiful", or anything similar, we thus are not coming anywhere closer to an objective, but instead just closer to a reproducible quantification. This, in turn, only shifts the power to define what is "good", "right", or "beautiful" to the person responsible for designing the respective algorithm. Thus, put simply, using such an algorithm, we simply trade our own subjective judgement for the subjective judgement of another person. In my opinion, this is something to keep in mind whenever we are discussing to which extent algorithms can or should be used in governance.

Related to this is the question why we even have such a desire for objectivity in purely subjective matters in the first place? Personally, I assume that such a need for objectivity might be the consequence of a distrust in one's own ability for judgement. Only if I mistrust my own opinion, I will get a desire to make sure to "feel the right thing." Such a desire, in turn, might result from insecurities that arise as a consequence of facing a complex, confusing, messy and uncertain world. This brings us to the next point.

Algorithmic judgement as an ersatz religion?

Towards the end of the book, an interesting analogy between religion and algorithmic judgement is drawn. It is mentioned that both of them can be used in an attempt to answer two big questions of humanity. These are: "What should I do?", and "Am I good?" Naturally, these questions are hard to answer -- provided we even are able to answer them at all. And naturally, religion is able to give a set of answers to these questions, and thus can provide a sense of security and certainty.

The argument that instead of a religion the judgement of an algorithm can also fulfill this basic human need and thus provide us with the same sense of security is compelling to me; even more so given the complexity of our modern world, in which trying to decide what is right or wrong can be demanding and stressful. The idea also fits nicely with the observation of our ever-increasing reliance on recommendation systems, the quantification of our self, and subsequent attempts at its optimisation.

However, a questions remains: How can a company even manage to enter and occupy such a position of power in the first place? This brings us to the last point.

Trading freedom for comfort

Also towards the end of the story, a little remark is made which I found particularly worth mentioning again: A power-hungry tech corporation on its own is not able to ever obtain any significant amount of power, unless we also collectively decide to exchange our privacy for comfort and lazyness. I think this is an important addendum to the debate regarding the power of Big Tech and how to limit it. Only if, and as long as, we willingly hand over privacy, and thus ultimately freedom, to some corporation because it makes our lives a bit more easy, said corporation is able to wield power over us.

Admittedly, laziness, a desire for an easy life and probably most importantly simple personal indifference are hard to overcome. Thus, it should not really come as a surprise anymore how powerful big tech corporations have already been able to become and continue to become.

The cynic in me also thinks that this is a potentially important lesson to be learned by everybody with a desire to found a start-up and to grow it into a powerful company: If one manages to free people from some tedious or boring task, they will willingly and gladly give up their money and personal freedom just for that little extra bit of comfort. Another cynical suggestion of mine would be to try to not only offer comfort, but also a sense of security. I am sure that a product that frees its customers from the demanding task of thinking independently, and thus also frees one from facing the consequences of a bad decision, will be very well received.